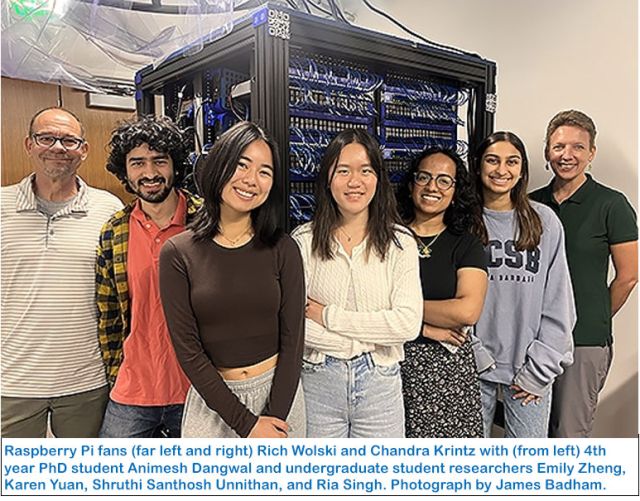

Krintz & Wolski "A (Very) Large Slice of Pi"

Oracle donates a cluster of 1,050 Raspberry Pi 3iPB+ computers to CS Profs Chandra Krintz and Rich Wolski's RACELab

From the COE News article "A (Very) Large Slice of Pi"

A few years ago, as a demonstration of the power of a relatively simple technology, software giant Oracle built a cluster of 1,050 Raspberry Pi 3iPB+ computers. The low-cost, low-power, credit-card sized machines are widely used, normally as individual units or in a small cluster of several units, to explore, learn, and teach computing and programming, and to perform certain kinds of research-related computational tasks. They are a favorite of hobbyists.

Now Oracle’s big cluster, the largest such assemblage ever built, has found a new home at UC Santa Barbara. About a year ago, computer science professors Chandra Krintz and Rich Wolski received the cluster as a donation from Oracle, which had retired it from making the rounds at computer trade shows.

Wolski explains: “The Raspberry Pi was designed to function with the Internet of Things [IoT]. It’s used for a lot of experimentation and deployment of fairly basic systems. They're very simple and inexpensive, they operate on very low power, you can program them using a large ecosystem of open-source software, and they are compatible with a wide variety of hardware devices and sensors.” It’s an interesting device, but on the low end of performance. “Oracle decided to do an experiment by building a large collection of these things in a small package. They would then ship the assembly to trade shows to show how effectively they were able to engineer a very big, very low-power, very low-technology system to run their software.”

Known for doing technologically advanced things, especially at the enterprise-scale and in the cloud, Oracle was trying to show that they could also do really small things, and do them super-efficiently. They used this collection of Raspberry Pi’s to demonstrate that, Wolski explains. “Eventually, they moved on to bigger and better things, and it wound up sitting in its crate in a warehouse. One day, the head of Oracle Research came to visit our lab, because one of our graduate students was doing an internship at Oracle, and he saw that we had a small set of Raspberry Pi’s in our lab, which we use in our research and as a teaching tool. He took one look at our little collection and said, ‘Do you need more Raspberry Pi’s?’

“If you're an academic and someone says, ‘Can I give you something?’ the answer is always, ‘Yes, absolutely, without another thought,’” Wolski says with a laugh. “And then this massive cluster arrived at UCSB.”

Chris Benson, who is now at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory but designed the cluster while at Oracle, stepped in to help Krintz and Wolski set up the system. “He’s been a world of help,” Krintz says. “He has come to campus multiple times to guide and advise us on the system. It turns out that a lot of the things Oracle was doing depended on access to Oracle engineers internally, so we’re now refactoring the machine to make it usable in a public institutional environment, with open-source software to enable broad access for students and others. Chris put the technology together in a way that had never been done before. It was coming to its end of life, and now it can live on in the service of computer science research and education here at UCSB.”

“The cluster was built differently, since it had to run for only a few hours at a trade show, than it would have been to support a PhD student’s research over multiple years,” Wolski continues. “We have learned over the course of the past eight months what needs to be done to turn this very interesting experiment into something that is a sustainable piece of research infrastructure.”

The size of the Raspberry Pi cluster (the second largest, built at Los Alamos National Laboratory, is half as big) has created a few challenges, especially in terms of cooling. “We did not have sufficient air conditioning for something this big in Henley Hall [the mostly naturally air-cooled LEED Platinum home to the UCSB Institute for Energy Efficiency],” Wolski explains. “We initially thought that we would receive maybe ten or twenty Raspberry Pi’s, fifty at the most. But we got one thousand fifty!

“The hardware runs at low voltages and, therefore, has a relatively cool heat footprint, but when more than a thousand of the units are packed together as tightly as these are, to make the cluster as small as possible, heat can build up,” he adds, “so, adjustments had to be made to adapt the cooling system in Henley Hall.”

"The fact that Oracle built this Raspberry Pi cluster to demonstrate their ability in using relatively simple technology to run their highly complex software speaks to how fortunate we are to now have that same cluster — the largest in the world — at UCSB," said strong>John Bowers, the Fred Kavli Chair in Nanotechnology, a Distinguished Professor in the departments of Electrical and Computer engineering and Materials, and director of the Institute for Energy Efficiency (IEE), where the Raspberry Pi cluster is housed. "I look forward to seeing what Chandra Krintz and Rich Wolski will accomplish with it going forward, both on the research front and in terms of the tremendous opportunity it provides students for studying the Internet of Things at a scale unmatched at perhaps any other university."

Since the Henley Hall AC upgrades, Krintz and Wolski have developed additional safeguards to prevent overheating. “If the temperature in the room starts to rise, emails and text messages go out,” he says. “We’re using our own Internet of Things research system to monitor the system, which was never designed for unattended operation 24/7. It’s a great challenge and a great research and learning opportunity.”

“Now, as part of our research efforts, we are figuring out what it means to make a long-lived, low-power data center,” Krintz explains. “For instance, we are developing new, intelligent scheduling techniques that place jobs across the system according to a heat budget. The system must also adapt to changes in voltage level that result from load on the power-distribution units. Our advances will account for these automatically to keep the system cool and balanced with regard to power draw.”

Solving the problems around the cluster fits right into the mission of the RACELab (The Lab for Research on Adaptive Computing Environment), led by Krintz and Wolski co-lead and dedicated to studying the IoT from a systems perspective. “The Internet of Things requires having computational infrastructure in strange places, such as in a closet in your home or a back room in a Starbucks, so it will have to be low power and easy to use — to make your coffee, for example,” Krintz notes. “That's the key point.”

Students in the lab are hard at work adapting the system. “They are building 3D visualizations for augmented reality, so that we can zoom in and say, ‘What's this Pi doing, and when?’” Wolski says. “We’d love to be able to click or zoom in on it and have it tell me, ‘I'm sick. This is my clock rate. This is what I'm running. This is the last time I was well,’ because we need a kind of health-and-status report at scale. We want to be able to look at any part of the whole 3D architecture and instantly identify any problems.”

“In our lab, we build the system software, we investigate new kinds of systems for managing IoT deployments, and we're very interested in how we go from very small devices — even smaller than Raspberry Pi's — all the way up to very large devices like the cloud,” Wolski explains. “A lot of our students are using this cluster, both as a large-scale machine and to simulate lots of small machines working together. We use it in many different ways as a test bed for things that we're going to deploy in the wild.”

The networked computing power of the giant Raspberry Pi cluster, Wolski says, makes it possible for their lab “to study these power and heat issues for the Internet of Things at a greater scale than anybody else in the world, providing an experience for students in our lab that, in many respects, is unique among universities. It's kind of remarkable. Oracle has provided us and the UCSB computer science research community with a rare and valuable opportunity.”